There once was little airline that flew primarily one route between the city centers of Cleveland and Detroit on tiny propeller planes, that catered mainly to businessmen (yes, 90% men), but also to grandmothers rushing to meet their new grandchild, couples house hunting after a job transfer, as well as celebrities.

"Singer Robert Goulet was appearing in a Detroit nightclub recently when he received an invitation to appear on a television show in Cleveland. The popular vocalist declined politely, explaining that his tight schedule would not give him time to make the trip.

Then someone suggested an airline called TAG. With flights every 15 minutes at peak hours, it would make Cleveland as accessible as a trip across town.

Arrangements were made. Goulet left his Detroit hotel, made a ten-minute drive to City Airport, a 38-minute flight to downtown Cleveland, taped the show, and was back in Detroit without missing as much as a rehearsal.

His experience, multiplied by 75,000 passengers a year, reveals the phenomenal success of TAG, by far the largest air taxi service in the world.” (an excerpt from the Sohio corporate magazine, February 1966)

By the mid-1950s, commercial aviation in the United States had developed into several categories based on relative size, responsibility, or type of route network flown. Largest of these were the dozen domestic trunk airlines: American, Braniff, Capital, Continental, Delta, Eastern National, Northeast, Northwest, TWA, United, and Western (bolded companies operated into Cleveland Hopkins International Airport (CLE) at the time). Pan American and Panagra were the international "flag carriers" that did not operate extensive domestic route networks. Next were the 13 local service carriers, of which Allegheny, Lake Central, Mohawk, and North Central operated at CLE. Their job was to connect smaller and mid-sized cities to the larger airports and the truck airlines. Other airlines operated to the territories of the United States including Alaska, Hawaiian and Caribair in Puerto Rico. There were freight companies like the famous Flying Tiger Line, as well as helicopter operators in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and even Cleveland (for a short while—a future article will explore that operation).

The smallest type of airline was the scheduled air taxi, also known as a third-level airline. They had to operate planes with less than 12,500 pounds gross weight to be exempt from CAB routing and rate approval. But, unlike the larger airlines, they could fly into any airport they chose. These carriers often began as a literal “air taxi” services, where a small aviation business, for example a fixed-based operator, would offer flights from a central airport to almost anywhere within a reasonable distance for a negotiated price. Sometimes traffic levels and popularity of a destination, e.g., the Lake Erie Islands from Port Clinton, grew into definite patterns and warranted the development of a simple timetable. Thus, scheduled air taxis were born, including Port Clinton’s Island Airlines which flew venerable Ford Tri-Motors to six destinations on a total route mileage of 25 miles—a true mini airline! These were the predecessor to the commuter airlines that thrived after the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978.

The Early History of TAG Airlines

Another scheduled air taxi in Ohio was TAG Airlines (Taxi Air Group) which was founded by William Knight in Cleveland in 1955. It operated floatplanes (one 10-passenger DHC-3 Otter and two 5-passenger DHC-2 Beavers) from Cleveland to Detroit, with the hopes of adding service to Toledo eventually. Up to five daily flights started in April 1956, from seaplane bases near Lakefront Airport (CEL, now BKL) in Cleveland and at the foot of St. Jean Street in Detroit. The service was expected to save at least two hours travel time between the cities versus train or automobile (a 90-mile flight versus a 170-mile land journey). However, the flights had not been able to operate during the winter when Lake Erie was frozen and TAG had lost money with the expense of moving aircraft south to Miami from mid-April to mid-November.

TAG had accumulated a debt of $200,000 ($2.23 million today) when it was approached by Ross E. Miller of the Miller Oil Company in Detroit, an enthusiastic pilot. He offered to buy one of the floatplanes and ended up buying the operating company instead and assumed the considerable loss, hoping for a tax write-off. After the deal was signed, the IRS did not agree, so the new owners had to take the loss. This was not a very auspicious start to Miller’s entry into the airline business!

Undeterred, Miller bought two eight-passenger de Havilland DH.104 6A Dove “luxurious executive airliners” (per the airline's marketing) and started serving Cleveland’s Lakefront Airport with four round-trip flights per day to Detroit City Airport (DET) in July 1957. The Dove was a popular aircraft and is considered to be one of Britain's most successful postwar civil designs, with over 500 aircraft manufactured between 1946 and 1967. The original schedule out of Cleveland was departures at 8:00 and 10:20 a.m., 4:15 and 6:35 p.m. Return flights took off from Detroit at 9:10 and 11:30 a.m. and 5:25 and 7.55 p.m. TAG operated out of a small passenger terminal at Lakefront Airport behind the airport’s old operations and administrative building at the southwest corner of the field.

This one route competed against five trunk and local service carriers, including United and Lake Central (flying from their respective cities’ much larger and more distant main airports, CLE and DTW), charged $14 ($156.22 in 2024 dollars) one-way fares versus less than $10 ($111.58 today) by the bigger companies, flew smaller aircraft like de Havilland Doves and eventually Piper Aztecs versus large modern aircraft. Yet the airline thrived mainly due to the more convenient service offered by TAG closer to the business centers of each city. TAG also offered hourly (or better) service and identified themselves more closely with the Detroit-Cleveland passenger market.

TAG’s Expansion & Aspirations for Growth

TAG Airlines cautiously expanded service based on natural connections between cities in the industrial heartland of the US. For example, service from Rockford, Illinois (RFD-the tool capital of the US) to Detroit (the auto capital of the world) began on April 1, 1958. It also added service to Akron Municipal Airport (AKC-the rubber capital of the US) to Cleveland on April 28, and to Detroit on May 5, 1958. Detroit to Chicago’s Meigs Fields (CGX) was also flown in 1959. However, by 1959, these routes were dropped in favor of its bread-and-butter Cleveland-Detroit service.

TAG began operations at Burke Lakefront Airport’s new mid-Century modern terminal in early 1962 and inaugurated the first night flights at BKL on February 5, 1962, taking advantage of the new FAA control tower and airport lighting system opened the previous month. By May 1962, TAG offered 12 weekday departures each way. The year-end passenger totals in 1959, of 20,767, and 23,700 in 1961, increased to 44,324 by 1963.

This success encouraged Miller to apply multiple times (1960, 1961, 1964) to the CAB for a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity. designating TAG as an integral part of America’s airline system. This would have allowed TAG to fly larger aircraft such as the 28-passenger DC-3. These applications were consistently rejected by the CAB, possibly due to objections from larger airlines like North Central which offered frequent competing service on the CLE-DTW route.

TAG continued expansion as an air taxi in 1965, with services starting from Cleveland to Columbus (6 flights to CMH) and to Cincinnati Lunken Airport (4 flights to LUK) on March 3, and from Detroit to the pair of Ohio cities on May 3. Passenger boardings reached a record 83,873 in 1965, partly attributable to the airline starting some services at the much larger CLE and DTW airports, allowing TAG passengers to make connections with other airlines. These new routes were flown by the first of 15 newly ordered Piper Aztec aircraft. The twin-engine, six-passenger aircraft had all weather capabilities, radio and de-icing equipment, and flew at 210 miles per hour with a full load of crew, passengers, fuel, and 200-pounds of baggage.

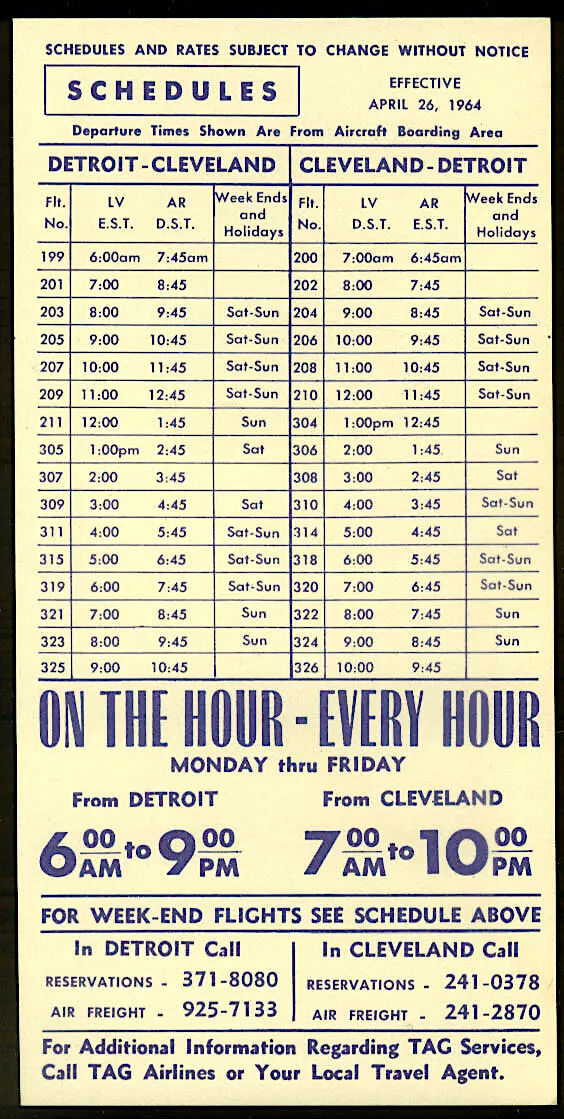

Service from Cleveland to Pittsburgh’s Allegheny County Airport (8 flights on weekdays and 2 on weekends to AGC) launched on January 3, 1966, followed by Columbus to Huntington, West Virginia (HTS) on January 17, 1966. Services from Detroit to Tri-Cities Airport (MBS) in Michigan was also scheduled to start on February 1, 1966, but I am uncertain if it ever did. However, at peak times—6:30 to 9:00 a.m. and 3:00 to 6 p.m.—TAG planes left Detroit City and Cleveland Lakefront airports every 15 minutes, more frequent than buses in the suburbs! (See images below of the TAG timetable from December 1, 1965, including flights from Cleveland Hopkins International Airport (CLE) and planned service to MBS, from www.timetableimages.com)

TAG “temporarily” suspended some 14 flights to Detroit from both BKL and CLE in January 1966, due to lack of sufficient revenue and a shortage of pilots. Flights to Pittsburgh and Cincinnati were then axed on March 2, 1966, with TAG citing “harassment” by the Airline Pilots Association (ALPA) and “impossible wage demands” by the union. Pilots set up an informational picket line at BKL to protest TAG’s unwillingness to negotiate a contract with 38 pilots represented by ALPA. Five pilots were to be laid off because of the cuts in service.

During 1966, Miller discussed with several aircraft manufacturers the idea of a new aircraft that would replace its aging Doves, seat up to 15 passengers, and still meet the 12,500-pound gross takeoff weight limit imposed on scheduled air taxis. Out of these talks developed the basis for the Beech 99 and de Havilland Twin Otter. TAG also expressed an interest in purchasing 40-seat Fokker F-27s, but the CAB still would not grant the airline a certificate. These plans were further frustrated when Gerald E. Weller, a former TAG sales representative, started Wright Air Lines on June 27, 1967, with service from BKL to DET in direct competition with TAG. As a result of these setbacks, all routes except its core BKL-DTW ended after October 1, 1967.

Miller also approached Les Barnes at Allegheny Airlines to discuss the possibility of an interline agreement, an agreement between two airlines to handle passengers when their itinerary involves travelling on those airlines. This allows passengers to book through-itineraries with less hassle than booking each flight segment separately. Barnes like the idea and the Allegheny Commuter System grew out of that meeting, although TAG never became part of this network. A third carrier attempted service on the BKL-DET route, Air Commuter Airlines, but it eventually merged with arch-rival Wright Airlines on March 4, 1968.

In March 1968, TAG finally received permission to operate larger aircraft, F-27s, to be followed by Fairchild-Hiller FH-227, but the certificate was revoked after objections from Wright, pending another CAB hearing. In the meantime, TAG became incorporated as a separate entity from the Miller Oil Company on June 28, 1968. Finally, TAG received its long-coveted Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity, albeit on a temporary basis for five years, on August 29, 1969.

A Tragedy Strikes TAG

Just after TAG was preparing to purchase three FH-227s in preparation to take on its main competitor, Wright Air Lines, a ten-year old TAG de Havilland Dove, N2300H, operating flight 730 from BKL to DET, tragically crashed into a frozen Lake Erie, fifteen miles offshore near Avon Lake, Ohio, on January 28, 1970. The plane took off at 7:38 a.m. climbed to 4,000 feet altitude, and disappeared from radar screens at 7:49 a.m. 20 miles northwest of downtown Cleveland.

United States Coast Guard rescue helicopters were quickly dispatched from Detroit and the wreckage was spotted at 9:28 a.m. with no signs of survivors. All seven passengers and two crew members perished in the accident. The Dove crashed into an ice pack 1.5 miles in diameter and was submerged in about 60 feet of water.

Flying conditions were reportedly excellent, though bitterly cold, and the pilot flying, Jake Feldman, age 43, of Parma, Ohio, the father of seven sons, was highly experienced with over 10,000 hours logged. Because of the harsh conditions this time of year, the salvage operations and investigation dragged on for months, keeping the tragedy in the public eye and negatively impacting the airline’s operations.

This was the first fatal accident in the 13-year history of TAG. Although, there was a close call in July 1959, when a TAG Dove lost one engine over Lake Eire after it caught fire, but the aircraft landed safely in Windsor, Ontario, Canada (YQG). The TAG crash was the second worst air disaster in Cleveland history. The worst was the crash of a United Air Lines DC-3 Mainliner on May 24, 1938. The flight from New York/Newark to Cleveland plummeted into a wooded farm ravine about a half mile north of Rockside Road in Seven Hills Village (today’s Brooklyn Heights), Ohio, around 10:17 p.m., killing all ten on board, seven passengers and three crew members.

The cause of the TAG accident was later revealed to be a manufacturing defect—metal fatigue cracks in the right wing, along with inadequate FAA replacement requirements, and not the airline’s fault. However, the NTSB did not publicize this finding until March 1971, further damaging TAG’s reputation and demoralizing its staff. A very similar accident occurred just 15 months later, on May 6, 1971, when an Apache Airlines Dove flying from Tucson to Phoenix crashed near Coolidge, AZ after suffering an inflight structural failure of its right wing, killing all twelve people aboard.

The Demise of TAG

In wake of the tragedy, TAG and Wright reached a preliminary agreement to merge on February 26, 1970. The deal involved Wright acquiring TAG for $3 million in cash and stock and was approved by both boards on March 23, 1970. Of course, the agreement would need CAB approval. It was hoped that the combined airline would finally be able to fly larger turboprop aircraft on the lucrative Cleveland-Detroit run.

While awaiting the CAB judgement, TAG continued to struggle greatly with passengers apparently scared off due to the crash (Wright Air Lines also experienced a decline in traffic.). During the February to May period, the airline saw a 75% drop in passengers year-over-year, with 4,963 in 1970 vs. 21,830 in 1969. In May 1970, TAG carried only 937 passengers compared to 5.444 passengers in the same month the previous year.

The fleet shrunk from 27 aircraft to two, flying ten round trips a day, compared to the 40 trips at the airline’s peak. These two aircraft passed a rigorous inspection required by the FAA, while another aircraft was grounded after inspection found a wing fitting crack.

In July 1970, the CAB turned down a proposed TAG-Wright merger, because it would weaken the supposedly financially stronger TAG. The airlines appealed this decision. On August 10, 1970, TAG suspended operations and furloughed all staff members, ostensibly for a 45- to 60-day period to give it time to reorganize as a scheduled air carrier as part of its proposed merger with Wright. Passengers dropped from 58,222 to 9,489 in one year.

In a stunning announcement on September 29, 1970, the CAB again rejected a merger between the two rivals and ordered TAG to resume operations within 90 days. This did not happen and the merger was officially called off in January 1971. TAG had hoped to find financing to allow it back in the air with 44-seat FH-227 turboprops.

By March 1971, with its valuable certificate in jeopardy, TAG and Boston-based Executive Airlines, the nation’s largest commuter airline at the time, carrying 400,000 passengers annually, proposed a merger. While awaiting CAB consideration, the companies proposed that Executive supply management services as well as three 40- to 44-seat turboprop aircraft to restart BKL-DET service, along with personnel to assist with marketing, human resources, and finances. TAG pledged to have hourly service restarted within 90 days of CAB approval of the preliminary plan.

Unfortunately, the deal fell through. TAG was out of funds, could not obtain new financing, and never flew again. On July 24, 1971, TAG surrendered its once-coveted certificate and went out of business as an air carrier. It owed both DET and BKL airports for landing fees and other charges, and the Detroit airport actually locked up TAG’s remaining five Dove aircraft.

Ross Miller, the great pioneer and innovator of the yet unborn commuter airline industry and co-founder of the Association of Commuter Airlines in 1963, never worked again in the airline business. He returned to his oil company and died in Toledo, Ohio, on August 28, 1990.

His little airline provided a vital link between downtown Cleveland and Detroit for over a decade as the “World’s Busiest Airline.” If it were not for the inflexibility of the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) and a tragic crash not the fault of the airline, TAG could have had a brighter future.

Look for a future article on TAG’s competitor, Cleveland’s own, Wright Air Airlines.

Thanks to R.E.G. Davies’ iconic volumes, Airlines of the United States since 1914 and Commuter Airlines of the United States, for much of the early source material for this article. The Cleveland Plain Dealer was also used as a source. For more interesting images of TAG Airlines click here for David H. Stringer’s article: https://avgeekery.com/the-company-that-called-itself-the-worlds-busiest-airline/

Comments